“Now we are nowhere” – In the Year of the Families, why aren’t we protecting the families that are falling apart?

We talk often about people enduring winter on the streets, but we forget to talk about those who are on the edge of the same fate, those still with a chance to be protected: We forget to talk about the families holding on tight at the edge of the rift while not getting any sensible help.

Panni and her partner lost their home when the foreign currency loan that took collapsed and the same thing happened to Mária and her family because of a small amount of unpaid debt. These are parents with several children who are trying to apply for a council flat, trying to give their children a decent upbringing, trying to get themselves together. Thousands of families like these could be saved from falling apart by a simple change of the law. This issue should be on the agenda instead of taking poor, ill people to court who are sleeping on the streets.

We meet the couple and their daughter in a shopping centre carpark out of town. It is a rainy November day and there is nowhere comfortable to go to talk. We end up sitting down on a bench in a secluded area. We can’t go to their place – there is no such thing. The parents of five had to leave their home in the Zugló area of Budapest due to having overdue bills and not being able to pay the 200-300,000 forints (€600-900) they owed. They had no idea they could ask to pay in instalments – the local family care centre didn’t inform them possible solutions. Since then, they have been living at the grandmother’s one-bedroom rented flat, paying 70,000 forints (€220) to her for a mouldy room where, according to the mother, it is impossible to provide proper conditions for the children.

She is deeply concerned by this. One of the children has developed asthma, the other children are frequently ill, too. Mária – let’s call her that – knows the difference now. Once she managed to rent a place “where it was possible to keep things tidy and clean, where there was hot and cold water and where the clothes could dry. In a mouldy place that is falling apart, all these things are impossible”.

Because of these conditions, child protection services have taken the children under protection and in the spring they may remove the nine-, ten-, 12- and 14-year-old children from the family (their oldest child, a boy, has since officially become an adult). They may take this action because, again, the family is facing eviction as the grandmother herself is in a great deal of debt. They don’t know where they could go. A period of five years where they have been unable to apply for a council flat because of a minor mistake on a form is about to end but, as we are about to see, even applicants with more experience are finding it hard to find a home.

Maria and her family have no hope of finding a home as no one wants to rent a flat to a family with multiple children, even though they could afford a modest one thanks to the temporary jobs they hold down. The parents are in a state of panic. They are terrified that when the moratorium ends and they are evicted, they will have nowhere to go, their children will be taken away from them and they will never be returned to them.

No way back

“They have good reason to be scared. Taking children back to the family step by step is uncommon.” – says Dr Zsuzsanna Győrffy, head rapporteur of the law in the Office of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights. It is she who presented last year’s comprehensive report examining child protection cases involving money issues in Hungary: “If a child is taken out of the family, then it is very likely that he or she is going to stay in the care system until officially becoming an adult.”

“They have good reason to be scared. Taking children back to the family step by step is uncommon.” – says Dr Zsuzsanna Győrffy, head rapporteur of the law in the Office of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights. It is she who presented last year’s comprehensive report examining child protection cases involving money issues in Hungary: “If a child is taken out of the family, then it is very likely that he or she is going to stay in the care system until officially becoming an adult.”

After the children are taken away, the family’s situation extends even further beyond hope; there is less chance they will be able to find a place in a temporary home for families, while the emotional distance between parents and children begins to grow. Keeping contact is often impossible because the parents have no money to travel and if the children are staying with foster families, the parents are not allowed to meet them in their home. They can only see them in a dull office somewhere and they cannot take them anywhere. The family falls apart, the parents stay in a homeless shelter while the children are either kept a foster family or at a children’s home.

According to child protection laws, no child may be removed from a family because of its financial situation alone, but the above-mentioned report by the ombudsman declares that despite this, in the areas examined the reason one third of children who are placed in care cannot go back to their families is because of their financial situation. But the state is not that strict with itself when it comes to the circumstances of the children it looks after. “A colleague of mine once asked a very relevant question: Can the children be taken away from the state due to financial issues?” says Dr Győrffy.

The care system seems unable to accord with the simplest protocols and rules (which are not too generous anyway). Children under the age of 12 should live with foster parents, yet many still live in crowded children’s homes. I myself once went to a home where instead of the maximum 12 allowed there were 19 children, with carers attempting to manage on such a small budget they could barely afford basics like toiletries. And yet they are still regarded as a financial burden on the state. The most recent figures are not available, but even back in 2013 the cost of a child in a children’s home was 210,000 forints (€650) a month and 91,000 forints (€280) when with foster parents. It’s worth noting that a foster parent is theoretically allowed to raise six children in total (including his or her own), but according to the professionals, there are foster families with ten or more.

So the question arises: Why can’t the situation of the family be fixed with the help of this large amount of money, which in the case of more children can go up to one million forints (€3,000) per month?

The consequences of a bad decision

The life of Panni Gyetvai and her family would be on track if a small fraction of the available funds helped them with their housing. Their example shows that there are thousands of families on the edge of the tragedy – families that we would not think could be in such a situation.

Their hardship began more than ten years ago following a string of unlucky coincidences and bad decisions. At the beginning of the 2000s, the family of four lived in their own flat in the Újpest area of Budapest. They had a business that provided a good standard of living. In building the business further and setting up a new one, they built up unpaid taxes and took out a loan to solve the problem. A few years later this loan was extended to be a foreign currency loan, recommended by a financial advisor in order to help their business grow further. For a few years everything went well. They managed to pay their instalments but in 2008 the business went bankrupt and at the same time their monthly instalments were doubled. Within a few months the family ran out of money.

They sold their flat at a loss to avoid it being auctioned by the bank. After a life’s work there remained only 1.5 million forints (about €1,500). They used this money to manage other debts and they paid for the rent a year in advance.

“We still haven’t been able to deal with this trauma,” says Panni. “Our children have been feeling down, too, and my husband owes the fact that he hasn’t developed a serious health issue to God and Jesus. There was no ground under our feet, we suddenly became homeless. Now we are nowhere.”

Until two years ago they had been renting a flat from a friend, who then transformed the place into an office. Since then the family sometimes shelters at an old neighbour’s, or at the husband’s mother’s home. Panni is caring for the old lady and they have a loving relationship, but the flat is too small for them to move in permanently. They can’t rent a place because even though the older children are now away, they have a six-year-old daughter and Panni would also like for her ill mother to live with them. This is the experience of the families living in difficult conditions: Families with children can’t rent because the owners are scared that if the family don’t pay the rent, they can’t have them evicted (the truth is they can and even during the time of the moratorium as you will see later in the article).

“There is nowhere we can be together,” complains Panni. “This is the reason why my older children left. I have been applying for a place for ten years, doing everything I could. I wrote letters to office workers and I spoke to many people: Mayors and their deputies, ministers and their wives. Many times, I felt confident that we would get a place that we had applied for only to be disappointed. Once we were banned from applying for two years due to an error we accidentally made on an income certificate. I became totally tired of this. I feel like there is no point in fighting. The most annoying thing is that I can see these empty council flats in the district all the time. We work, raise our child consciously and we were never involved with the child protection services.”

The council’s responsibility

Dr Győrffy mentions a long-forgotten proposal that could be motivating enough for the councils to help the situation of the families: “If the council of the area from where the child to be put in care were to pay for 25% per cent of the costs, there would be more thought given to how to solve the family housing problem.”

At the moment there is no such intention, unfortunately. Fanni Tóth, activist for the organisation A Város Mindenkié (The City is for All), has witnessed many situations where councils have put families out onto the streets, not paying attention to the fact that the eviction meant the destruction of the family. And just a little addition about what a child in a situation like this can expect: If the process of removing the child from the family does not happen before the eviction, then the child protection worker who arrives alongside the executor takes the traumatised child to a temporary collection centre, where a report is written about his or her circumstances within 30 days. There is no immediate psychological help; the overworked social workers can’t pay enough attention to the child. Sometimes there is not enough room – even though the number of places is restricted to 40, the place is required to take in all children, even if that means there are 60 of them.

The last resort of homeless families is often Temporary Family Homes, but the waiting list for these institutions can be up to six months, and those who have just been evicted don’t necessarily have priority. These institutions don’t provide a permanent solution for these families that a council flat would.

“The original purpose of these homes is to solve the temporary problem of living arrangements. But if you think about it, they are only an alternative to homelessness. Children grow up while their families are circulated around these institutions by the system. The only solution would be the development of the council flat system – experts working in the field have been raising this for a long time. There is also a need for social workers who can help the families live an independent life. But all these investments seem little compared to how much it costs for the state to support the individuals in a family, and most children living under protection will become just like their parents: They won’t become taxpayers, but they will be in need of the same support of the state for the rest of their lives,” says Dr Győrffy.

Campaign for the families

A Város Mindenkié aims to lawfully prevent these issues. It would guarantee that families with children cannot be evicted without being looked after at the same time by making two amendments to the law. “One of the proposals aims to amend the implementation law and applies to evictions from council flats and evictions due to mortgage related problems. This would not allow eviction to happen until the court makes sure that the family has somewhere to go. The other one aims to include in social law that the responsibility of the housing belongs to the council,” explains Tóth.

“The main point of this is that in case eviction happens the council must provide the family with a liveable and decent place in the area – of course in this case the family have to take steps, too, for example paying the bills properly. Developing the system of social council flats is necessary for all this to happen.”

This wouldn’t be such a new thing really, but it would ensure that the intent of child protection laws are carried out: No child should be removed from a family due to the family being poor.

These proposals were created by lawyers and have been put forward by Parliamentary opposition several times, but so far without success. The petition and the campaign on the platform of aHang has now moved up a gear in the hope that in the spring parliamentary sessions – and before the release of the moratorium – amendments could be voted for by Parliament. The campaign, called Stopkilakoltatás (Stopeviction), aims to show everyone how different kinds of families are affected and that arranging housing for them is the only solution from a both human and economical points of view.

A genuine face of all this is Fanni Tóth, who experienced the instability caused by losing her home as a child and as an adult as well. Along with others of her generation, her housing circumstances are still not stable: “I spend more than half of my salary renting a room. If anything were to happen to me, if I don’t have a job for a month, I can become homeless. And I’m a well-educated, middle class youngster from the city.”

Fanni was ten years old when the land on which her family home was built was auctioned due to a thoughtless third-party guarantee her grandparents arranged. Their situation got better when they managed to move into a council flat. Ten years later, Fanni arrived in an unstable situation again, this time because of the irresponsibility of her parents: They divorced and moved away from the city, leaving Fanni and her younger sister in the council flat owing hundreds of forints of overdue expenses. She put her student loan into paying off the debt, leaving her with nothing. Or maybe she still had a little: “I’m lucky because my friends paid for a ticket to Scotland for me, where I could start a new life. After that I came home and I live and work in Budapest, but I haven’t managed to finish university.”

According to official data, 22 families are evicted every day in Hungary. Families with or without children; old people, young people, educated people and non-educated people; people with foreign currency loans and squatters. Evicted because of outstanding debts or lost renovation bills, from a privately owned flat or from a council property. Each family has its own story and most of these stories we don’t know about: the eviction of families living in rented properties, or families living in properties to which they have no right, are not documented. Getting rid of them is not restricted by the moratorium either.

In a video on aHang you can see and hear one of the many stories. The Stopkilakoltatás campaign, the aim of which is to ensure by law that at least the families with children are protected, has started to show everyone there is a human solution. We just have to want it enough.

More than two thirds of Hungarians (69%) are opposed the eviction of families with nowhere to go. Just one fifth (21%) hold the view that eviction should be carried out even if it means families will end up on the streets (source: Policy Solutions and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung survey).

Translated from the original article by Anna Kertész

Pictures:

- 1: Dr Zsuzsanna Győrffy

- 2. “Many times, I felt confident that we would get a place that we had applied for only to be disappointed.” (photo: Dániel Kováts)

- 3-4-5.: Panni Gyetvai and her family (photo: Dániel Kováts)

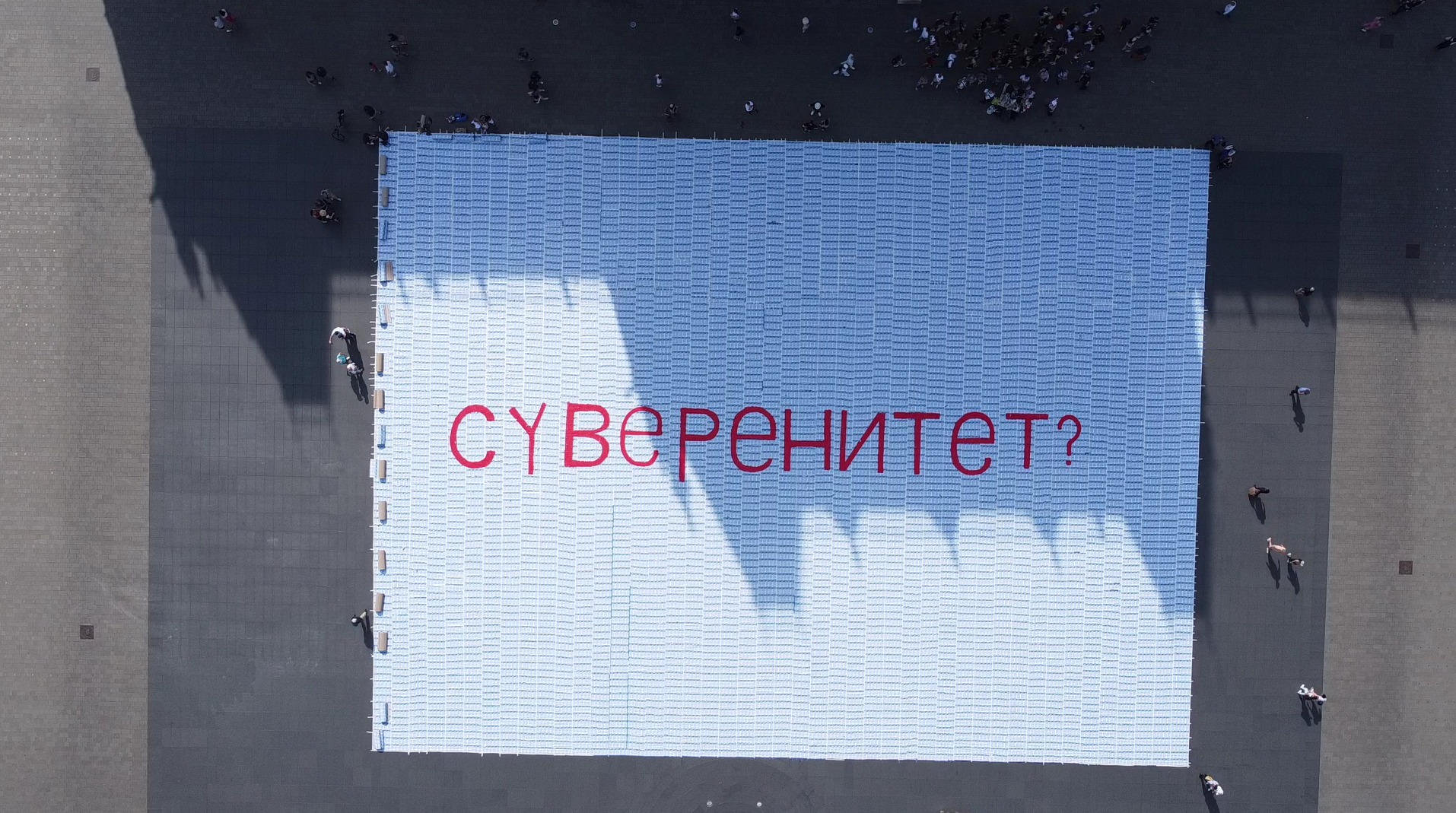

- 6. Fanni Tóth at a demonstration at Kossuth Square (Photo: Anna Vörös)

- 7. Photo: Anna Vörös